Shaping Industrial Geography: The Environmentalist Third Rail

Michael Whelan

Transportation shapes not only the housing and commuting patterns of people, but also the production and storage patterns of industries. In the early 20th century, railroads encouraged concentration of industry. This concentration changed with the transition to a trucking economy, which fostered industrial sprawl.[1] Yet contrary to this trend towards trucking, some states have implemented economic development programs to encourage industry to grow their use of direct railcar freight service. In this blog post, I argue that these programs, conceived in economic development terms, ought to be embraced by environmental advocates as a mechanism to encourage a greener transportation system. This goal can be met by shifting freight traffic to a less carbon-intensive mode and supporting a more climate-friendly geography of compact industrial development.[2]

Industrial Geography and State Action in the 20th Century

While in New York City earlier this year, I went for a stroll down the High Line from Hudson Yards to 14th Street (Figure 1). Since it opened as an aerial public park in 2009, the High Line has become an icon of New York, included on must-visit tourist lists alongside much more longstanding sites like the Empire State Building or Central Park.[3] No one should be surprised by this warm reception; walking the High Line is a sublime experience. But unlike the other flaneurs promenading above Chelsea, my High Line experience was tinged with wistfulness for the bygone geography of industry that built such an impressive piece of infrastructure in the first place.

Figure 1. A Walk Along the High Line[4]

The New York Central was one of the largest American railroads operating in the northeast during the late 19th century, known for its “Water Level Route” from New York to Chicago via the shore of Lake Erie.[5] By the early 20th, the railroad was facing a problem. It served a busy cluster of vertical factories and warehouses on Manhattan’s West Side with street-running tracks.[6] Frequent pedestrian crashes along the 11th Avenue route had inspired the nickname “Death Avenue”[7] and in 1929, the New York Transit Commission approved an order to remove all grade crossings on the route.[8] The plan was for an elevated viaduct that would serve industry above street level. In accordance with an enabling act passed by the state legislature in 1928 that allowed the state’s Transit Commission to plan and order the closure of grade crossings,[9] the cost of $30.7 million was split with $12.28 million payable by the state, $3.07 million by the city, and $15.35 million by the railroad.[10] At the route’s opening in 1934, Mayor LaGuardia responded “Amen” to a toast to the “Death of Death Avenue.”[11] Nor was safety the only thing celebrated: Speakers at the dedication emphasized that the new line would greatly increase “efficiency in the handling of New York’s daily supplies of milk, meat and other foodstuffs, much acceleration of West Side traffic, and a tremendous impetus to the real estate, commercial and industrial values of the entire West Side, and an extensive park development.”[12]

The High Line[13] was thus a public-private development project that accomplished multiple goals for the parties involved, including improved safety, a better public realm, and growth of urban industry. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: The High Line’s freight terminal in 1934, when it opened with space for 150 railcars.[14]

The High Line did not last long. After the Second World War, the geography of industry changed in America as new highways enabled an expansion of trucking.[15] In this new paradigm of economic geography, the vertical warehouses and factories of the West Side were increasingly outcompeted by land-intensive facilities near suburban highway exits. In 1960 – just 26 years after opening – the southern segment of the High Line was decommissioned.[16] The last train on the remaining segment ran in 1980[17] and the structure sat vacant until neighborhood activists mobilized to turn it into a park.[18] Today, New York City is more truck-dependent than any major city in America.[19]

The High Line illustrates how different technologies produce different spatial arrangements of commerce.[20] Railroads concentrated industry along corridors radiating from clusters at major junctions, where cities sprang up. The invention of the freight elevator[21] further intensified land use as these factories went vertical (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Western Electric Complex, 1936[22]

Unlike those transportation technologies, expressways inverted the economic factors favoring concentration by encouraging freight to shift to trucks, thereby fostering a dispersal of industry and warehousing. Dense cities led to congestion, best avoided by siting a factory near a new freeway ramp. While the capital intensity of railroads had encouraged recycling trackside land to new uses when old businesses failed, the flexibility of trucking dramatically expanded the number of “greenfield” sites available for siting entirely new industrial facilities outside existing urban areas.[23]

From environmentalist and urbanist perspectives, this meant disaster. Trackside towns lost industry that gave them a discernible center.[24] In cities, luckier industrial neighborhoods like Manhattan’s West Side were mothballed, which at least preserved them for eventual rejuvenation as housing.[25] Less-fortunate quarters fell to urban renewal, demolished to be remade for the trucking economy.[26] The highway logic that decentralized industry decentralized people to the suburbs too. Cities hollowed out.

This was a policy choice. Just as the High Line had been enabled by state and city investment, sprawl depended on enormous government investment.[27] The rail industry adapted and remains important today for long-distance intermodal and commodity shipments. However, it is direct carload service to trackside customers, not intermodal distribution from suburban railheads, that brings the greater decongestion and environmental benefits.[28] Growth in the carload freight sector would foster a more environmentally sustainable built environment by reasserting a centralized and radial geography that bolsters urban form against sprawl.

Industrial Geography and State Action Today

Some states have established policies that incentivize the carload freight sector. For example, Massachusetts established its Industrial Rail Access Program (IRAP) in 2012.[29] This capital investment program recognizes that often a nudge can shift industrial shippers from truck to rail – maybe a siding hookup, or a layover track, or extending an industrial track a few hundred feet (Figure 4). Without incentives, the potentially large startup cost discourages switching to rail, even if shipping that way is cheaper once established.

Figure 4. Rail Customer’s Siding Expanded with IRAP Funds[30]

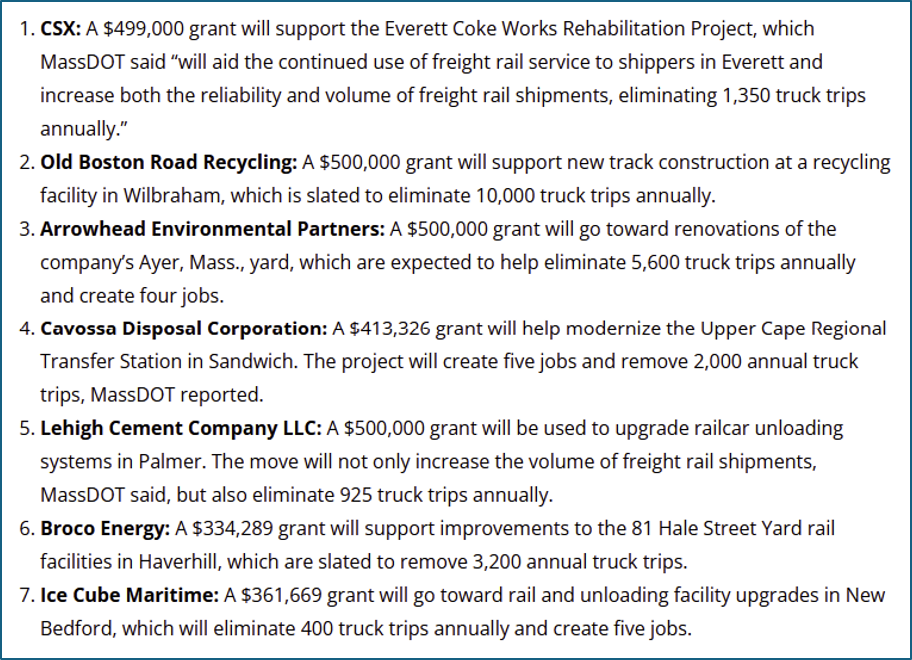

IRAP spends just $2-3 million annually. It gives out grants of no more than $700,000 by paying no more than 60% of project cost, but that bump can tip the scale towards direct freight service.[31] Though the program is small, repeating it annually steadily adds new customers to the rail network, or expands the use of existing customers (Figure 5).[32]

Figure 5. 2022 IRAP Awardees[33]

With incentives encouraging increased carload freight, industrial tracks and branch lines that seemed slated for abandonment are revived. Short trains out of local yards grow a bit longer. Trucks are taken off the road.[34] Subtly, the industrial geography of the state starts to look more sustainable, resilient, and urban.

While our built environment will likely never return to the dense multi-storied industry of early 20th century Manhattan,[35] IRAP demonstrates that just as the public purse was used to build highways that flung industry across the landscape, it can be used to tilt industrial geography away from dispersion and back towards more concentrated land use. IRAP harkens back to the 1929 order from the New York Transit Commission that split the cost of grade separation between the government and railroad.[36] Distributing cost between industrial shippers and the government sets the program apart from roadway investments, which are generally funded entirely by government spending.[37]

Massachusetts is not the only state that has set up this kind of public private partnership for capital investment in carload freight rail. Virginia’s Rail Industrial Access (RIA) program funds grants of up to $750,000 per project with a required 30 percent match by the applicant.[38] Maine[39] and North Carolina[40] have similar programs aimed at hooking customers up to the network. While other states may not have programs for rail customers, many have matching programs for railroads themselves to rehabilitate tracks, which could make it more attractive for industrial shippers to use their services.[41]

Mental Shift on Mode Shift[42]

By encouraging a shift towards a lower-emission mode of transportation and towards industrial land uses that are more compact, these programs could be considered environmental grants. Yet they are not generally framed that way. For example, the Massachusetts statute that authorizes IRAP declares that “the purpose of this program is to provide funding for projects that increase access to rail freight service and preserve or stimulate economic development through the generation of new or expanded rail service.”[43] The program was passed as economic development legislation, not environmental law.

This is perhaps not surprising. When policymakers, pundits, or activists discuss decarbonizing the transportation system, they often focus on electrifying passenger cars. Mode shift is neglected, and freight is doubly neglected. Furthermore, the environmentalist movement (perhaps especially the legal environmentalist movement) has traditionally focused on preventing industry from doing things. Many major federal environmental statutes function by slowing down or halting building projects.[44] When a Norfolk Southern train derailed in East Palestine, Ohio three years ago, toxic chemicals burned onsite for days afterwards.[45] In light of rail incidents like this, do environmentalists really want to encourage this industry?

As counterintuitive it may seem, the answer is yes. Scaling up IRAP-like programs could catalyze two vital changes: a mental shift among environmental lawyers and an incentive shift in the capital structure of the railroad industry.

First, the climate crisis can only be tackled by building new infrastructure. A leading environmentalist recently wrote that we need to build “solar panels and wind turbines and factories to make batteries and mines to extract lithium” while advocating a shift away from reflexively saying “no” to new infrastructure.[46] He added that we also need “new affordable housing that will make cities denser and more efficient while cutting the ruinous price of housing.”[47] The country’s spatial status quo is a 20th century paradigm of fossil fuel-driven automobility and sprawl.[48] Environmentalists should want to change that.

Second, the rail industry will not grow its shipment volumes or compete with trucking if it is not incentivized to do so. The rail industry is organized into regional duopolies and tends to have highly activist shareholders who focus intensely on profit margins, which can be increased by means other than growing traffic volume.[49] Encouraging the railroads to compete for truck traffic requires modifying the inventive structure. Minimizing the capital cost involved for carload freight infrastructure has seen success in Massachusetts and other states. States that are interested in not only electrifying our existing transportation paradigm but in transitioning to a more sustainable economic geography should follow their lead, and environmentalists ought to support them when they do.

Conclusion

Nearly one hundred years ago, the public and private sector came together to bring efficient and direct rail freight service into the heart of America’s largest city. While our economic geography will likely never reach the levels of density and concentration we saw in that era, some degree of concentration is necessary if we are to ensure that land use itself – and not just vehicle power – shifts towards a greener future. The latest iteration of public-private partnerships to grow carload freight may not have had such grand ambitions; the stated intent of IRAP was economic development. But it points to a productive template. Environmental policymakers should consider making a new alliance with economic development advocates to marshal government and the private sector behind projects that are good for the environment and for growth. It is time to elevate our ambitions for carload freight.

[1] Uday Schultz, Industrial Sprawl, Home Signal, (Dec. 25, 2020), https://homesignalblog.wordpress.com/2020/12/25/industrial-sprawl/.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, Carbon Dioxide Emissions in the Transportation Sector, at 10 (Dec. 2022), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-12/58566-co2-emissions-transportation.pdf (trucking emissions are eight times higher than rail emissions per ton-mile); Schultz, supra note 1.

[3] See, e.g., Things to Do in New York City, N.Y., Tripadvisor, https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g60763-Activities-oa0-New_York_City_New_York.html (High Line appears sixth on list of top New York City attractions) (last visited Mar. 27, 2025).

[4] Photo by author.

[5] About N.Y.C., New York Central System Historical Society, https://nycshs.org/about-n-y-c/ (last visited Mar. 27, 2025).

[6] West Side Plan Wins Approval of I.C.C., N.Y. Times, Dec. 12, 1929, at 22, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1929/12/12/issue.html (West Side Line served with 400 cars in each direction daily, including milk and perishable freight).

[7] ‘Death Ave.’ Ends as Last Rusty Rail Goes; Huge West Side Improvement Completed, N.Y. Times, June 26, 1941, at 25, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1941/06/26/87634941.html?pageNumber=25.

[8] West Side Crossings Ordered Eliminated, N.Y. Times, Feb. 21, 1929, at 23, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1929/02/21/95735783.html?pageNumber=23.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Mayor Dedicates West Side Project, N.Y. Times, June 29, 1934, at 1, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1934/06/29/93761914.html?pageNumber=1.

[12] Id.

[13] At the time of construction, the new elevated line was known as the “West Side Improvement Project” or “West Side Project.” For the ease of contemporary readers, I apply the term “High Line” throughout.

[14] Id.

[15] Richard F. Weingroff, Moving the Goods: As the Interstate Era Begins, Fed. Highway Admin. (Sept. 8, 2017), https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/interstate/freight.cfm.

[16] Freight Yard to Shut, N.Y. Times, Jan. 30, 1960, at 9, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1960/01/30/99725647.html?pageNumber=9.

[17] Zoe Rosenberg, Inside St. John’s Terminal: A Look at One of NYC’s Most Ambitious Redevelopment Projects, Curbed (Jan. 20, 2017), https://ny.curbed.com/2017/1/19/14286628/st-johns-terminal-inside-pictures-nyc.

[18] History, The High Line, https://www.thehighline.org/history/ (last visited Mar. 1, 2025).

[19] Jessica Gould, New York’s Roads Are Trucked Up, WNYC (Oct. 12, 2019), https://www.wnyc.org/story/new-yorks-roads-trucked-up/.

[20] Edward Glaeser, Urban Colossus: Why Is New York America’s Largest City?, FRBNY Econ. Pol’y Rev. 7, 19 (2005).

[21] The Starrett-Lehigh Building’s elevators carried freight cars up to 19 factory and warehouse floors. Jiyoon Song, The Economic Impact of the Preservation and Adaptive Reuse of Rail Tracks, the High Line in New York City: Regional Impact Analysis and Property Value Change Analysis 14 (Aug. 2013) (M.A. thesis, Cornell Univ.).

[22] Western Electric Complex, NYC (1936), Wikimedia Commons, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d3/Western_Electric_complex_NYC_1936.jpg.

[23] Glaeser, supra note 20, at 19; Greenfield vs. Brownfield: What’s Better for Your Manufacturing Facility?, Gray (2025), https://www.gray.com/insights/greenfield-vs-brownfield-whats-better-for-your-manufacturing-facility/.

[24] See, Edward Glaeser & Janet E. Kohlhase, Cities, regions and the decline of transport costs, 83 Papers Reg’l. Sci., 197, 211 (2004).

[25] See, New York City Landmarks Pres. Comm’n, Gansevoort Market Historic District Designation Report, 18-19 (2003).

[26] New York City Dept. of Trans., Reimagine the Cross Bronx Expressway: Final Vision, 20-21, (March 2025).

[27] Tom Hanchett, The Other “Subsidized Housing” Federal Aid to Suburbanization, 1940s-1960s, in From

Tenements to Taylor Homes: In Search of Urb. Hous. Pol’y in Twentieth Century Am. 163, 163-164 (2000).

[28] Jonathan English & Uday Schultz, Railroads Help Cities Reduce Highway Truck Traffic and Cut Air Pollution, Bloomberg (Nov. 28, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-28/railroads-help-cities-reduce-highway-truck-traffic-and-cut-air-pollution.

[29] Industrial Rail Access Program, Mass.gov, https://www.mass.gov/industrial-rail-access-program.

[30] MassDOT Announces $18 Million in Grants for Freight Rail Projects, Progressive Railroading (July 11, 2018), https://www.progressiverailroading.com/rail_industry_trends/news/MassDOT-announces-18-million-in-grants-for-freight-rail-projects–55083.

[31] Mass. Dep’t of Transp., Rail & Transit Div., Request for Applications: Industrial Rail Access Program FY25, 4, (2024) https://www.mass.gov/doc/industrial-rail-access-program-irap-fy2025-application-instructions/download; Jonathan English & Uday Schultz, Railroads Help Cities Reduce Highway Truck Traffic and Cut Air Pollution, Bloomberg (Nov. 28, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-28/railroads-help-cities-reduce-highway-truck-traffic-and-cut-air-pollution.

[32] See, MassDOT Awards $3MM in Industrial Rail Access Grants, Railway Age (Sept. 9, 2022), https://www.railwayage.com/regulatory/massdot-awards-3mm-in-industrial-rail-access-grants/.

[33] Id.

[34] Tim Murray, Murray: Freight Rail Common Good for Commonwealth, Boston Herald (Mar. 20, 2024), https://www.bostonherald.com/2024/03/20/murray-freight-rail-common-good-for-commonwealth/; Massachusetts Railroad Association, Industrial Rail Access Program, (2022) https://www.massrail.com/industrial-rail-access-program (“Success stories” include projects that increased carloads, volume, and employment).

[35] Edward Glaeser & Janet E. Kohlhase, Cities, regions and the decline of transport costs, 83 Papers Reg’l. Sci., 197, 220 (2004).

[36] West Side Crossings Ordered Eliminated, N.Y. Times, Feb. 21, 1929, at 23, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1929/02/21/95735783.html?pageNumber=23

[37] L.D. Solomon, Macquarie and the Privatization of Highways in the United States, in The Promise and Perils of Infrastructure Privatization, 83 (2009).

[38] Rail Industrial Access Program, Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, https://drpt.virginia.gov/our-grant-programs/ria/.

[39] Economic engine | A state grant program promotes business expansion while strengthening Maine’s aging rail infrastructure, MaineBiz(May 10, 2004), https://www.mainebiz.biz/article/economic-engine-a-state-grant-program-promotes-business-expansion-while-strengthening.

[40] Rail Industrial Access Program, North Carolina Department of Commerce, https://www.commerce.nc.gov/grants-incentives/public-infrastructure-funds/rail-industrial-access-program.

[41] Appendix 2, Freight Rail Economic Development (FRED) Study (Nov. 2013), Minnesota Department of Transportation, https://www.dot.state.mn.us/ofrw/fred/PDF/appendix2.pdf.

[42] In the context of decarbonization, “mode shift” refers to shifting trips from motor vehicles to greener forms of transportation. It is most often used in the context of personal mobility, focused on shifting car journeys to walking, cycling or transit. (See, e.g., What is the transport mode shift?, SWARCO, (2025), https://www.swarco.com/stories/what-transport-mode-shift.) However, the concept can be extrapolated to freight, where it would entail shifting truck traffic to rail.

[43] Mass. Regs. Code tit. 700, § 4.01, 700 MA ADC 4.01.

[44] Nicholas Bagley, The Procedure Fetish, 118 Mich. L. Rev. 345, 354 (2019).

[45] Tom Perkins, Chemicals from East Palestine Derailment Spread to 16 US States, Data Shows, The Guardian(June 19, 2024), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/jun/19/east-palestine-toxic-derailment-chemicals-spread.

[46] Bill McKibben, YIMBY, NIMBY, and the Progressive Struggle for Clean Energy Infrastructure, Mother Jones (May 2023), https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2023/04/yimby-nimby-progressives-clean-energy-infrastructure-housing-development-wind-solar-bill-mckibben/.

[47] Id.

[48] See, Robert Harris, How America became so car dependent, CNBC, (Feb. 13, 2025) https://www.cnbc.com/2025/02/13/how-america-became-so-car-dependent.html (“About 92% of U.S. households have access to a car. But only about 55% of Americans have access to public transit. And only about 3.5% take advantage of the options available”); Oliver Milman, How Extreme Car Dependency Is Driving Americans to Unhappiness, The Guardian (Dec. 29, 2024), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/dec/29/extreme-car-dependency-unhappiness-americans.

[49] Thomas Black, Guess Who Loses When Railroads and Investors Unite?, Bloomberg(Sept. 19, 2024), https://www.envoy.cirrus.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2024-09-19/guess-who-loses-when-railroads-and-investors-unite?srnd=undefined.